Western State Hospital is located on the site of historic Fort Steilacoom, which served as a military post from 1849 to 1868 until the federal government abandoned it. The Washington territory purchased the fort with the intent of turning it into a hospital for people who suffered from mental illness. The hospital, then called the Insane Asylum of Washington Territory, opened in 1871 with 15 male and six female patients.

In 1889, when Washington was granted statehood, the hospital was renamed Western Washington Hospital for the Insane. The hospital was renamed again as Western State Hospital in 1915.

As times changed for the new state of Washington, so did methods for treating the mentally ill admitted to Western State Hospital. Hydrotherapy was the early treatment of choice. Wet packs, hot tubs and showers were used for nearly 50 years to create a calming effect for the patients. Insulin therapy was started in the mid-1930s, followed by electric shock therapy. A surgical procedure called the frontal lobotomy was used for a period of time. It was later replaced with psychotropic drugs, counseling, and behavior modification therapies, practices that remain in use today.

Western State Hospital was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and Washington Heritage Register as the Fort Steilacoom Historic District on Nov. 25, 1977.

HEATH FARMSTEAD

Joseph Heath, who emigrated from England to Canada, arrived in 1844 and leased 640 acres from the Puget Sound Agricultural Company. Heath built the Heath Farmstead and lived on the land until his death on March 7, 1849. He raised cattle, oxen, horses and sheep on the land and farmed potatoes, wheat, beef, mutton and wool.

FORT STEILACOOM

The U.S. government leased 20 acres of the land (for $50 a month for 20 years) from the Puget Sound Agricultural Company and created Fort Steilacoom in August 1849, where it remained an active U.S. military installation until 1868. It was an influential presence as headquarters in the construction of early road systems, as a supply depot and refuge, solidifying the U.S. presence during the Puget Sound War of 1855–1856 and serving as a social center for the area’s early settlers and visitors passing through the region. The fort underwent two development periods in 1849 through 1853 and 1857 through 1858.

Angle Lane SW is among the roads built during the military use of Fort Steilacoom. It was created as a route across the Cascade Mountains through Naches Pass to access Fort Walla Walla. From 1856-1859, several buildings were constructed that would become the core of the future Western State Hospital and the creation of a military road from Fort Steilacoom north to Fort Bellingham.

The military abandoned Fort Steilacoom on April 22, 1868, as the need for such an installation had waned with the end of the Civil War and regional conflicts with Native American tribes.

The Washington Territory began acquiring land for what would become Western State Hospital in 1868, although land acquisitions continued for many years until the final parcel was purchased in 1947. The Washington Territory bought 26 buildings at an auction on Jan. 15, 1870, and the U.S. War Department authorized donation of the Fort Steilacoom site to the territory later that year.

AGRICULTURE

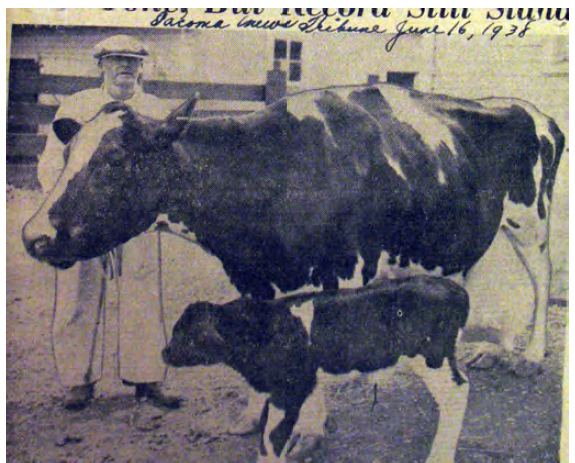

Farming is an important aspect in the history of Western State Hospital and continued until 1965. During the hospital’s farming heyday, the campus had more than 1,200 fruit trees (apple, cherry, plum, pear), 20 acres of vegetables, a dairy and a stable of animals that included 60,000 chickens, 2,200 turkeys and ducks, 800 hogs and hundreds of cattle. The prize of this herd was Steilacoom Prilly Olmsby Blossom, who lived from 1921-1938 and produced a world record 258,210 pounds of milk containing 9,558 pounds of butterfat during her lifetime. Although the hospital no longer does large-scale farming, it still operates a greenhouse where patients in the recreational therapy program tend to the plants.

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY

Occupational therapy has long been a treatment staple at Western State Hospital as a way to reduce patient frustration and the need for medications and physical restraints. Male patients worked the farm, repaired shoes, made furniture and during World War II, picked crops at neighboring farms due to worker shortages. Female patients worked in the sewing room and made shirts, aprons, dresses, linens, pajamas and more. The sewing program continued through the 1950s. Occupational therapy has evolved over the decades, and now focuses on helping patients set goals and succeed in meaningful roles in their lives through independent activities of daily living and leisure.

RECREATION THERAPY

During his time as superintendent, Dr. John Wesley Waughop made an effort to change the perception of the hospital as a prison for those suffering from mental illness to that of a treatment hospital. He created programs that organized music, singing, dances and games for patients. By 1898, the hospital had sufficient in-house staff and patient talent to form a small orchestra. By 1898, the hospital provided evening dances every Saturday during the summer. Patients were also allowed to take chaperoned excursions away from the hospital, which included walking, riding and fishing at the lake.

Outside groups visited the hospital to give theatrical performances and live music while patients had recitals and sang songs. The hospital also started its own baseball team in 1898 and played its games on an on-campus baseball diamond complete with grandstand. Recreation therapy, too, has evolved over the years and includes activities such as playing board games, playing sports, fitness and arts and crafts.

NOTABLE EARLY LEADERS

Dr. Stacey Hemenway (1871-73)

Dr. Hemenway served as the institution’s first resident physician. The wards were utilitarian spaces heated by large box stoves with sheet iron drums. Windows were equipped with iron rods for security. Bathrooms were equipped with hot and cold water and separate dining areas served the two genders.

Dr. John Wesley Waughop (1880-97)

Dr. Waughop oversaw the early development and build-out of the hospital. He oversaw the construction of Western’s first administration building and the construction of a central kitchen, a powerhouse, a laundry and three additional wings for a total of nine new wards. The new buildings were meant to help with the ongoing problem with escapees. The lack of security at the old fort buildings proved a constant difficulty.

By 1887, the hospital extended to 638 acres and included five male wards, three detached dormitories, two female wards, an office and dispensary, a commissary, two dwellings, a carpenter shop, three blacksmith and tin shops, a stable and carriage house, a cow barn, a stove house, a kitchen and a bakery, an assembly hall, dining rooms, two laundries, a piggery, a poultry house, eight wood houses and two tank houses.

A 1906 plaque at the hospital includes a quote from former Gov. Albert Mead stating that Waughop was the “practical creator of the institution as it now exists. Through his professional attainments, his executive ability, and his intelligence as a man, the institution was built up and took high position among those of the country.”

Dr. William Keller (1914-22, 1933-49)

Dr. Keller led WSH through World War I, the global 1918–1919 influenza pandemic, the Great Depression and World War II. He oversaw extensive building campaigns in the 1910s and early 1920s as well as the near rebuilding of the campus in the 1930s. He also developed services for patients, contributed extensively to mental health research, new treatments, the landscaping, farm development and beautification of the grounds.

He brought a forward-looking program to Western intent upon furthering research and reducing the social stigma of mental illness through greater interconnections with the surrounding community. At the time of his appointment, he did not have psychiatric experience, but had worked as a hospital administrator. In 1919, he hired the hospital’s first woman doctor, Dr. Mary Perkins.

During his second stint as superintendent, Dr. Keller oversaw the construction of a new administration building, several wards, a new morgue and several farm buildings. In 1933, the institution undertook the first steps in providing social services for patients, which included follow-up on those patients who had been temporarily released.

The following statement from Dr. Keller became the hospital’s motto during his tenure:

“The Western State Hospital is dedicated to mental health. A sound mind and a healthy body is not only the greatest asset of an individual, but also of the community and the nation. ’Tis the mind that pilots us through life.”